A time of day, dawn, made sharp by anticipated interruption; a house

animated by children, their happiness, their demands, their balloons and

playthings; the potential for violence innate in all beauty, as well as

the awful beauty of violence; the feeling of elation at filling a house

with the clacking of a typewriter, and the fear of the silence when the

typing ends: these elements are my personal “Ariel,” and I tire of the

more rhetorical and showy poems—“Daddy,” “The Applicant,” “Lady

Lazarus”—upon which Plath made her notorious name. “Ariel” ends with a

poem, “Words,” about the season that T. S. Eliot called “midwinter

spring” and Wallace Stevens called “the earliest end of winter”: March,

when, in New England (a region all three poets share), the sap runs.

Plath’s keystrokes in the quiet house are like “Axes / After whose

stroke the wood rings.” Before, echoing away from her, they become like

horses’ “indefatigable hoof taps”—“riderless,” as in a funeral

procession. Add to the available accounts of Plath (there are so many)

this, please: nobody brought a house to life the way she did. “Ariel,”

despite the tragedy that attends it, is a book with much joy between its

covers.

-

Dan Chiasson

|

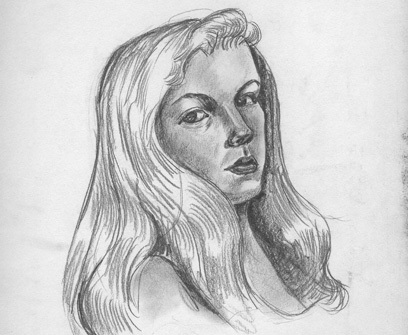

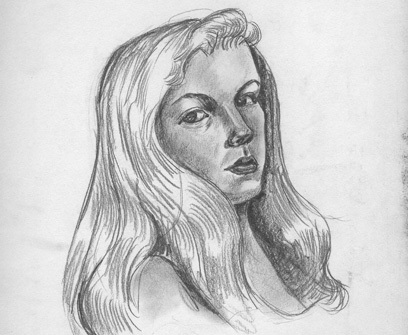

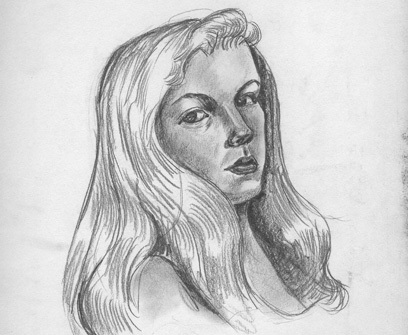

| Sylvia Plath, self-portrait |